Georgia Prisoners in Black and White

Barry Godfrey Professor of Social Justice, Liverpool University

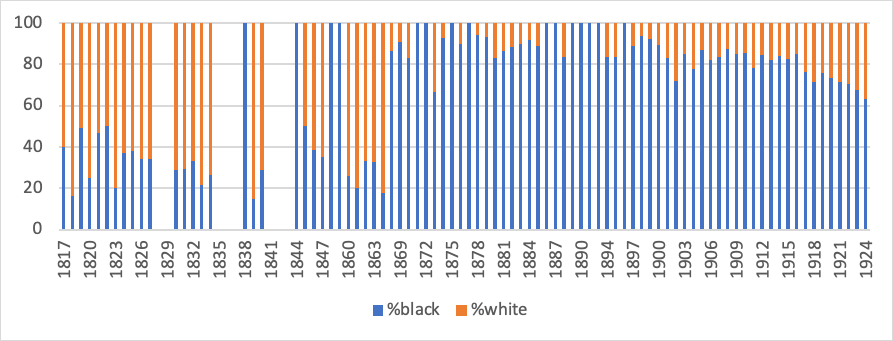

Recent analysis of Georgia Penitentiary records by Steven Soper and Barry Godfrey show that there was a significant rise in the number of formerly enslaved people who were imprisoned following the end of the Civil War. In Georgia before the war there was an average of forty people a year being sent to prison. One such person was prisoner Samuel W. Whitworth, described as ‘fair’ of complexion, blond, blue-eyed, 5 feet nine inches tall, from Jones County. The cotton farmer, originally from North Carolina, was gaoled for causing ‘mayhem’ (probably some drunken violence) on March 10th 1817, and sentenced to ten years imprisonment. He managed to escape on Christmas Eve 1820, and had three years on the run, before being re-captured and hanged in South Carolina in December 1823. As a white man, he was in the majority whilst he served his time in a Georgia prison. Between 1817 and 1865, the records of complexion reveal that four-fifths of inmates were described as ‘white’, ‘fair’, or ‘light’; and a fifth were described as ‘black’, ‘dark’, or ‘copper’ coloured. From 1868 the category of ‘race’ replaced ‘complexion’ in the records, giving the records a spurious pseudo-scientific gloss, though terms such as ‘ginger cake’ (used for nine hundred people) reveal the impressionistic and casually derogatory basis of the descriptors.

Georgia Prison system reception by ‘race’, 1817-1923 (%)

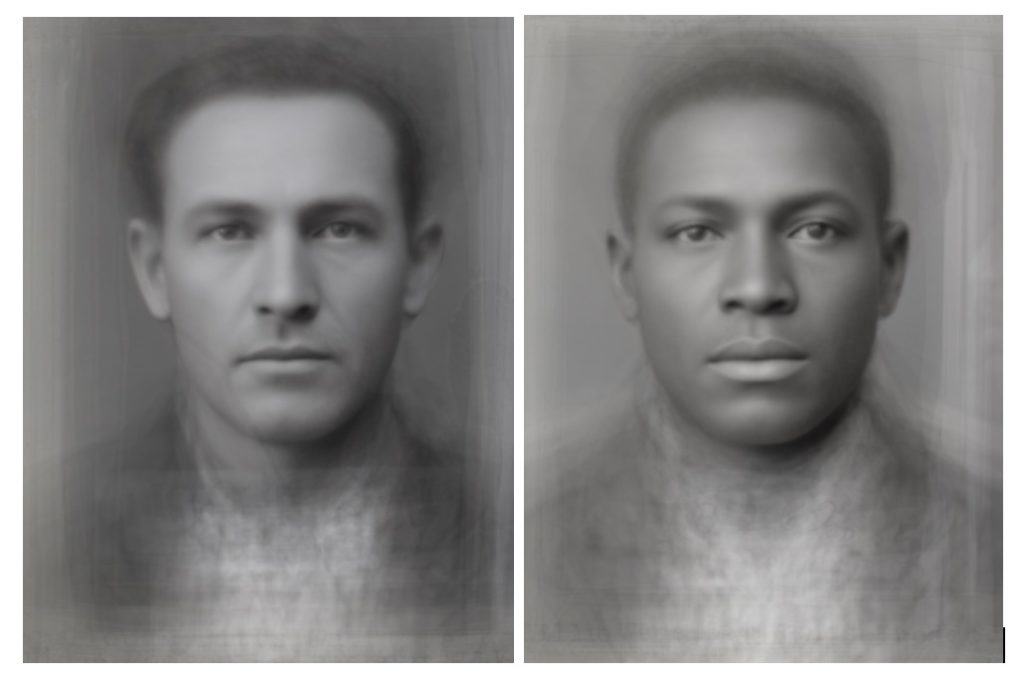

Statistics can only take us so far. The digital composite photographs constructed by Jessica Liu and shown in the exhibition more dramatically capture the shift in prison demography.

Pre and post average faces of Georgia convicts

In Georgia, the prison population reflected racist policies operated through the criminal justice system, and the legacy of the over representation of African Americans can still be seen in Americas prisons today. It seems we now have access to evidence which shows the long-standing use of prison as a tool of oppression against the poor, and particularly the African-American poor.

Caroline Wilkinson, in her lecture which accompanies this exhibition, further explores cognitive and other biases which continue to play out in the criminal justice system, and in society.

Using methods developed in the “Digital Panopticon” (which provides huge amounts of data on British convicts) Steve Soper and Barry Godfrey have used digitised trial reports, census records, prison documents, and family histories in order to reconstruct prisoners’ lives, before and after they were imprisoned in the system. Some of these stories of people convicted of theft, murder, drug-and alcohol-running are revealed in the exhibition. However, wherever possible, our research tells the story of people after they were released. We believe that people should not be defined either by their status as formerly enslaved people, or as prisoners of the new Georgian penal estate. They spent time in prison, but, when released, they re-built their lives. For example, Claud Leavell, who was born the son of a farm laborer in Carollton, Georgia, 1903. During the First World War In WWI, he presented himself at Fort McPherson in Atlanta to enlist. Although he was only fifteen years old, he was allowed to join up as he had given his age as nineteen. He served his country until 1919, when he was given an honorable discharge. Three years later, struggling to find work after being discharged, he was convicted of transporting liquor contrary to Prohibition legislation, his first and only conviction. By the time WWII started, Claud was employed and living in Detroit with his wife Maria. Like many people, he worked hard to overcome the stigma of being a former-convict, and battled other forms of discrimination, to make a new life. The stories in this exhibition do as much to honor their struggle as much as condemn the system that made struggle necessary.